간행물

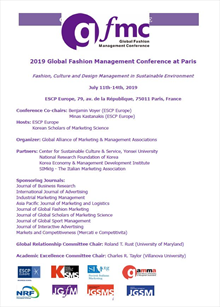

Global Fashion Management Conference

- 발행기관 글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

- 자료유형 학술대회

- 간기 부정기

- ISSN 2288-825X (Print)

- 수록기간 2015 ~ 2024

- 주제분류 사회과학 > 경영학 사회과학 분류의 다른 간행물

- 십진분류KDC 325DDC 330

권호리스트/논문검색

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna (2017년 7월) 192건

141.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.416

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

The personal luxury goods market in the Middle-East is the 10th largest in the world, right before Hong-Kong and Russia, which are both well-established markets for luxury products (D’Arpizio, Levato, Zito & Montgolfier, 2015). However, luxury consumer behavior consumption in the Middle-East and its influencing factors have largely been left unexplored. This paper builds on previous research among German luxury consumers and investigates the formation of brand love and its impact on willingness-to-pay among Arab luxury consumers. Compared with the German study, it is found that Arab luxury consumers show weaker brand love tendencies. In addition, materialistic characteristics and tendencies for conspicuous consumption among Arab consumers strongly influence brand love in the context of luxury fashion and accessories, which confirms previous findings. Results further document that for Arab luxury consumers neither conspicuous consumption tendencies nor brand love can be interpreted as a predictor for an increase in willingness to pay. Hence, for those consumers, long-lasting emotional consumer-brand relationships are not responsible for generating additional profits and do not explain why the willingness to pay for luxury goods was significantly higher among Arab consumers. Finally, results indicate that though some elements of luxury consumption are shared among German and Arab luxury consumers (e.g. fashion involvement, the evaluation of particular brands, gender and brand love tendencies) there are significant differences in terms of e.g. brand preferences, general willingness to pay for luxury fashion and accessories and willingness to pay for conspicuous luxury goods. This research provides insights into the formation of brand love among Arab luxury consumers and how it informs luxury consumption. Moreover, it sheds light on similarities and differences across the two samples and increases the understanding of luxury consumption in a broader geographic context.

142.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.417

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Brand prominence has emerged in the last years as a promising research area in luxury marketing. The present research looks at extending our current understanding of the role played by the conspicuousness of a brand’s trademark or logo on consumers’ purchase intentions. Drawing from qualitative (semi-structured interviews) and quantitative (online questionnaire) research methods, we explore the impact of logo size (small vs. large) and nature of products (high street vs. luxury) on consumers’ attitudes towards products, intention to buy and willingness to pay. The explorative qualitative part features semi-structure interviews to understand luxury consumers’ opinions on brand prominence. The quantitative part features a 2 (prominence: low vs high) x2 (luxuriousness: high street vs luxury) mixed factorial design. Participants are first presented with images of t-shirts with varying logo sizes (small vs large; prominence: low vs high) and varying brands (luxuriousness: high street vs luxury) before answering a series of questions in relation to their products and brand preferences. This research carries both theoretical and managerial implications. In terms of theoretical implications, it contributes to a better understanding of brand prominence, and the difference between high street vs luxury brands in terms of consumer perception. In terms of managerial implications, it can help marketers to optimise the size of a logo and brand name depending on the nature of the brand they work with.

143.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.418

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

The luxury branding industry thrives on creating products and services that are exclusive in nature. To achieve this, brands often control for pricing, quality, quantity and availability to create a perception of exclusiveness. The literature showcases a handful of concepts to explain how marketers can create exclusive products and services. However, the literature does not give a theoretical foundation to the creation of the Theory of Exclusivity. This study is the first to address this issue. A number of theories and concepts in marketing, psychology, sociology and other fields of sciences have been reviewed to conceptualise the Theory of Exclusivity. The conceptualisation of this theory gives marketers a better understanding of how they can create exclusive brands.

144.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.419

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Ever since sustainable development was brought up in the United Nation in 1987, sustainability has been one of the top priorities in the policy making process of different governments as well as different companies. Despite the fact that different industries have been putting efforts in promoting sustainability in their business, little effort was initially shown in the luxury industry. The sector has been regularly criticized by the general public for its lack of sustainable development imperatives. This has led to an extensive discussion in the academic field on whether luxury and sustainable development are by nature compatible or not. Some scholars suggest that the two concepts are indeed able to co-exist as they share many similarities. They suggest that virtual rarity is the key to increase the motivation of luxury consumers for sustainable luxury purchase. However, no further studies have concerned the relation between virtual rarity and sustainable luxury. It is the objective of the present paper to challenge this hypothesis, confronting it with the market perspective. Studying the views of Western regular luxury consumers towards the two concepts should ultimately help luxury managers design more efficient, and hopefully effective, strategies to promote sustainability in their companies. To achieve this objective, the paper is organized into the following parts. First, a thorough literature review helps defining the concepts of virtual rarity and of sustainable luxury, and ultimately merges both. Then, the qualitative methodology to conduct the study is explained, along with a detailed description of the methods used for data collection and data analysis. The paper then focuses on the most important theoretical and managerial findings, still acknowledging further research developments due to research limitations.

145.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.420-424

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Introduction For the past decade, luxury brands have become increasingly interested in portraying themselves as purveyors and curators of a “luxury lifestyle” (Dauriz & Tochtermann, 2013). Some of the world‟s largest fashion brands, for instance, have expanded their offerings to include lifestyle products and services such as housewares, furniture, fine dining, hotels, and private residences (e.g., Ralph Lauren, Giorgio Armani, Bottega Veneta, Hermès) (Mellery-Pratt, 2014). Given that “lifestyle” is now one of the major buzzwords in luxury marketing (Dauriz & Tochtermann, 2013), it is useful to attempt to provide a solid theoretical perspective on this topic. The objective of this paper is to deepen our understanding of “luxury lifestyle” in a contemporary context. To do so, we first examine the existing definitions of lifestyle as a marketing concept. Next, we link the concept of lifestyle to customer segmentation and provide an integrative conceptual framework on lifestyle segments within luxury marketing. Finally, we highlight key insights and important lessons concerning luxury lifestyle segmentation for both theoretical and practical applications. Literature Review Multiple definitions of lifestyle exist in the literature. In this paper, we focus on the major accepted definitions. The concept of lifestyle was first introduced by Lazer (1964) in marketing research. According to his pioneering work, lifestyle is a distinctive mode of living, embodying the aggregative patterns that develop and emerge from the dynamics of living in a society. Building on this notion, Plummer (1974) specifically conceptualized lifestyle as a unique behavioral style of living that includes a wide range of activities (A), interests (I), and opinions (O). His AIO framework served as an important building block in the development of lifestyle scales as shown in Table 1. Table 1. A Summary of Lifestyle Scales Since the introduction of Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1973), the concept of lifestyle has been combined with personal values as exemplified in VALS (Mitchell, 1983). According to Schwartz (1994), values are one‟s desirable, relatively stable goals that serve as guiding principles in life. In other words, values contribute to the formation of a certain lifestyle (Gunter & Furnham, 1992) in that: (a) values are transsituational in nature influencing a wide range of behaviors across many different situations; and (b) individuals prioritize their world views based on their values varying in importance (Seligman et al., 1996). In the context of consumer behaviour, values are commonly regarded as the most deeply rooted, abstract consumer traits explaining how and why consumers behave as they do (Vincent & Selvarani, 2013). In line with this perspective, we thus conclude that luxury lifestyle is a multi-faceted construct focusing on a luxury consumer’s personal values manifested in the consumer’s activities, interests, and opinions. Conceptual Framework We propose a new framework of luxury lifestyle segmentation, including Conspicuous Emulators, “I-Am-Me” Uniqueness Seekers, Self-Driven Achievers, Hedonistic Experientials, and Societally Conscious Moralists, based on the review of related literature (e.g., Mitchell, 1983; Vigneron & Johnson, 2004; He, Zou, & Fin, 2010). The description of each segment and related firm strategies are shown in Table 2. Table 2. Lifestyle Segmentation Framework for Luxury Marketing Discussion and Implications Lifestyle is now the focal point for the marketing activities of most luxury firms (Dauriz & Tochtermann, 2013). In this study, we focused on the concept of lifestyle, one of the most compelling and widely used approaches to luxury market segmentation. Our conceptual framework built on the notion that luxury markets are heterogeneous, consistent with prior research describing the heterogeneity of luxury consumers (e.g., Vigneron & Johnson, 2004; He, Zou, & Fin, 2010). Since the 1960s, lifestyle has been viewed as a key marketing concept and has been the focus of a significant part of the market segmentation literature. The basic concept of lifestyle has not been greatly altered. Many of the fundamental approaches to lifestyle research are still valid today. The essence of the AIO approach outlined by Plummer (1974) is still evident in the work by Ko, Kim, and Kwon (2006) that defines a fashion lifestyle. Other advances in lifestyle research use personal value theories to specify different consumer segments. Despite the underlying stability of the basic concept of lifestyle, recent advances in digital communications and social media platforms and the trend toward globalization are introducing a discontinuous change to the adoption and implementation of segmentation strategies in luxury markets. Information technology has dramatically affected the nature of the communication and distribution options for luxury firms. As exemplified in specific industry examples in Table 2, consumers now interact with luxury firms through myriad touchpoints in multiple channels and media. These changes are altering the concept of luxury lifestyle segmentation. Thus, there is much room for additional research to strengthen the overall conceptualization of luxury lifestyle segmentation. One important topic involves the question of whether specific lifestyle segments prefer specific forms of touchpoints. For example, Hedonistic Experientials may prefer social media platforms whereas, for other segments, traditional vehicles such as print advertising and flagship stores may still remain crucial. Given a sizable and growing number of global luxury brands, another important issue for future research is to investigate whether the five lifestye segments conceptualized in this study can be empirically replicated on a global scale. We conclude that the concept of lifestyle segmentation, once adjusted to reflect the impact of the digital revolution and the globalization of luxury brands, has a great potential to advance both theory and practice in luxury marketing.

4,000원

146.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.425-430

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Shopping is a sensory experience for consumers, who use cues, such as shelf organization and stock levels to infer the luxury and perceived scarcity of the given product or brand. Therefore, affecting consumer’s perceptions, evaluations and purchase intention. This research holds implications for brand, retail and merchandising managers.

4,000원

147.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.431-432

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

With the development of information technology, the market situation is changing more rapidly than ever. The change is most rapid in the preferences and lifestyle of consumers. For companies to survive in such an environment, it is indispensable to develop innovative and competitive new products by better understanding the needs of consumers. Any novel and meaningful idea of a new product basically originates from knowledge, which plays an important role in the performance of new products because it is the most valuable asset for a business entity. In this study, the author considers the knowledge sharing process as a dynamic aspect based on the term “knowledge,” carrying a static meaning as used in the existing research. The nature of the knowledge sharing process pertaining to new product development has been largely divided into three terms and then re-established. The author focuses on a new product development team as the subject of sharing and providing knowledge on new products, and regards the solution to problems that may arise in the development process as the stability of the team. The moderating effect was examined by the relationship between the type of knowledge sharing process and the outcome of the new product with the variable of team stability. The results indicate that the convergence and similarity of the knowledge sharing process affect new product performance as positive variables, whereas the tacitness of the knowledge sharing process does not lead to a significant result in terms of performance of new products. This study also shows that the stability of the team has a positively direct effect on the outcome of the new product. Thus, the convergence process of various kinds of knowledge positively affects the diversity and innovation of new product concepts. Moreover, the same recognition area or shared goal awareness and sense of responsibility play important roles in the performance of the new product. The moderating effect of team stability between the type of knowledge sharing process and new product performance is described in the convergence and tacitness of the knowledge sharing process. In the process of merging existing knowledge with new knowledge or sharing embedded knowledge in the members with, the activity wherein the members of the NPD team communicate and collaborate with each other over a long period of time will provide opportunity to improve the performance of the new product. The purpose of this paper is to examine the relationship between the type of knowledge sharing process, the stability of the team, and new product performance. Academic and managerial implications and the directions for future research are discussed as well.

148.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.433

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

149.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.434

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Overseas R&D subsidiaries contribute to the cross -border knowledge sourcing of MNC headquarter by providing tacit and context specific knowledge and reducing the searching cost of the headquarter

150.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.435-438

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

This study develops a framework that links commitment, relationship investment, relationship learning, functional conflict and innovation orientation to innovation. This framework has three main features. First, it examines the direct effects of commitment and relationship investment on relationship learning. Second, it examines the direct effect of relationship learning on innovation. Third, it investigates the moderating effects of functional conflict and innovation orientation on the relationship between relationship learning and innovation.

3,000원

151.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.439-444

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Introduction The current fashion industry has been overrun with fast fashion products in the last couple of decades. Consequently, it has become one of the most environmentally degrading industries worldwide, and is plagued by social and economic inequalities (Fletcher, 2013). The fast fashion apparel industry produces pollution and waste; and wearers are exposed to hazardous materials. The fast pace of the fashion industry has also led to unsafe working conditions that can result in detrimental influence on workers as in the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Furthermore, the individuals responsible for making the fast fashion products often live in underdeveloped countries and are paid below national minimum wage (Niinimaki, 2013). In contrast, the sustainable fashion industry aims to produce safer, cleaner, and more impactful apparel. A part of the growing sustainable apparel industry is slow fashion, which emphasizes creating fashion products at a less-intensive pace with environmentally-minded techniques. Slow fashion movement is an emerging trend within the fashion industry that counteracts the harms of fast fashion. The term „slow fashion‟ was first used by Kate Fletcher and shares several characteristics with slow food, from which the slow fashion movement got much of its inspiration (Cataldi, Dickson, & Grover, 2010). Slow fashion is thought to represent a blatant discontinuity such as a break from the values and goals of fast (growth-based) fashion (Fletcher, 2013). Slow fashion attempts to remedy the various negative economic, social, and environmental global impacts of the current fast fashion system. The purpose of this study was to analyze the material-oriented trends of representative fast fashion and slow fashion brands toward the development of sustainable fashion. This study aimed to answer the following questions: 1) By what efforts in terms of material usage do the fast and slow fashion brands promote sustainable fashion? and 2) How do these efforts influence apparel manufacturing as sustainability practices and consumers‟ purchase intentions? Backgrounds Moore and Fernie (Moore & Fernie, 2004, p. 31) defined fast fashion as “various strategies to respond commercially to the latest fashion trends”. Fast fashion brands, such as H&M, Forever 21, and Zara, use a combination of quick response and enhanced design techniques to quickly design, manufacture, and stock trendy apparel and accessories that consumers can purchase at an affordable price (Cortez et al., 2014). The manufacturers of fast fashion brands struggle to provide innovative merchandise in their preferred production timetable (Cortez et al., 2014). In such an overloaded manufacturing process, the apparel industry has experienced increased pollution and hazardous work environments. Slow fashion is defined as “a philosophy of attention that is sensitive to environmental and societal needs and to the impact production and distribution have on society and the environment” (Karaosman, Brun, & Morales-Alonso, 2016). Antanaviciute and Dobilaite (2015) report that the slow fashion industry is sustainable and seeks a greater purpose than making profit, and is thus characterized with promoting fair economic, environmental, and social systems within the fashion cycle. In the slow fashion movement, the materials used to produce garments are environmentally friendly. Sustainable fashion is achieved when available materials are used to their ultimate potential; waste materials are utilized; the products are recycled; and a second life for the fashion products is planned (Sharda & Mohan Kumar, 2012). In addition, sustainable fashion uses biodegradable materials such as organic cotton, polylactic acid, and other biopolymers etc. (Fletcher, 2013). In the production phase, garments workers who produce sustainable fashion products are paid a living wage, unlike their counterparts who work for less than a dollar a day in the fast fashion industry. Throughout the slow fashion supply chain, reducing the speed at which the products are produced and consumed is emphasized. Slowing down the production phase results in end products of better materials, with more material-construction input-time, and longer-lasting overall final product, as compared to typical fast fashion items. Case study This study was conducted based on a case study. We analyzed the sustainability practices in aspect of fiber materials of two representative brands: a fast fashion, Zara and a slow fashion, People Tree. Several resources were used to collect the information necessary for the case study. The primary resources were academic articles, reports, and brochures from companies‟ websites. The information on both companies was very useful to understand their products and sustainability practices as a fast fashion and a slow fashion brand. Zara is a ready-to-wear fast fashion retailer based in Spain, which was created by Rosalia Mera and Óscar Pérez Marcote in 1974. Since its creation, the fast fashion retailer has built a reputation for manufacturing and stocking on-trend clothing at the customer‟s demand. The company sends small shipments year-round to stores and subsequently monitors the customers‟ reactions by adjusting the store inventory. The retail giant has employed over 10,000 employees and is a private company that, according to the Business of Fashion, was worth $16.7 billion in 2013 (Hansen, 2012). Zara is known as affordable luxury (Gamboa & Goncalves, 2014) for its on-trend imitations of high-end clothing pieces that are inexpensive. The average Zara consumer is young with an age range of 18 to 24 years and female (Gamboa & Goncalves, 2014). Zara was chosen for this case study based on its unique and successful fast fashion business model. Zara has been criticized for numerous violations in manufacturing practice, including a lack of hygiene and safety in its Argentinian factories. The workers‟ rights NGO La Alameda, alleged that the working conditions consisted of no breaks and poorly lit and unventilated conditions (Crotty, 2013). The company compensated the workers and was forced to pay $530,000. People Tree is considered as a pioneer in the slow fashion movement and sustainable fashion. The company has implemented many measures to increase its economic, social, and environmental sustainability. People Tree was the first fashion brand to develop an integrated supply chain for organic cotton from the farm to the final product. Furthermore, they were the first organization to achieve a Global Organic Textile Standard certification. They source their yarns, fabrics, and accessories locally, as well as choose natural and recycled products over the toxic, synthetic, and non-biodegradable materials typically found in fast fashion products. The People Tree producer group is comprised of over 4,560 artisan producers, which includes hand weavers, hand knitters, embroiderers, tailors, and group leaders. They allow local individuals to produce and create incredibly unique products, thus generating livelihoods and incomes for these individuals who typically reside in very rural areas. Zara uses a variety of synthetic and organic fibers and textiles in its clothing. Zara partners with a company called Lenzing to source recycled polyester, cotton, and wool when available, and then donates any extra textiles not used in manufacturing products. Zara prioritizes using organic cotton and recycled materials. Organic cotton is grown and manufactured without harmful pesticides. Zara has become one of the biggest users of organic cotton, which is a part of their Join Life campaign and in collaboration with the Better Cotton Initiative (Inditex Annual Report, 2016). Zara also uses three types of rayon in its products: Modal, Viscose, and Lyocell. These materials are made from cellulose fibers, which take longer to harvest and manufacture than cotton. People Tree does not use polyester in its products, and most of its clothing is made from organic cotton and wool. It uses 100% fair-trade certified organic cotton that is certified by Soil Association (People Tree Seventh Biennial Social Review, 2011-2012). In addition to cotton and wool, it uses a fiber called “Tencel,” which is made from wood pulp. Tencel is a Lyocell product, also made from cellulose fiber, which is stretch-resistant and highly versatile. Zara uses both synthetic and organic fibers; whereas, People Tree uses organic fibers in the manufacturing of products. Lyocell is one of the most revered sustainable fibers currently on the market. Lyocell is a cellulosic fiber, specifically derived from wood pulp, normally eucalyptus (Fletcher, 2013), beech, and pine (Gordon & Hill, 2015). In a typical process, the wood pulp is dissolved in a solution of amine oxide, a solvent, which is then spun into fibers; subsequently, the solvent is removed from the fibers through a washing process (Fletcher, 2013). The manufacturing process recovers 99.5% of the solvent and the solvent is recycled back into the process (Fletcher, 2013). The solvent is non-toxic, non-corrosive, and all effluent is non-hazardous (Fletcher, 2013). Lyocell has many other environmental benefits such as complete biodegradability (six weeks in an aerated compost heap), and of renewable raw material (eucalyptus has a fast-growing cycle and reaches full maturity in seven years). No bleaching is used prior to processing the fiber, thus reducing chemical, water, and energy consumption in the dyeing process; hence, Lyocell is considered as a “very clean” fiber (Fletcher, 2013). While Lyocell is considered a very sustainable product, its production is energy intensive. However, due to recent research, the amount of energy used to make Lyocell has begun to decrease (Fletcher, 2013). Lyocell is also known by its brand name, Tencel (Gordon & Hill, 2015). Companies such as People Tree have begun to use products like Tencel in their everyday-clothing production. People Tree‟s “Our Tencel” collection is produced by Creative Handicrafts, a social enterprise working to actively empower disadvantaged women of the slum communities of Mumbai through economic independence. Like every producer of People Tree‟s clothing or Tencel products, Creative Handicrafts works to provide fair pay and safe treatment for all their workers. They also work to improve the lives of those employed by Creative Handicrafts. People Tree is currently using their “Our Tencel” collection to upskill the workers, making them qualified for higher paying and more difficult jobs should they choose to leave Creative Handicrafts. They aim to provide workers with a greater range of fabrics that they can work with for future client‟s needs. This provides the workers with greater business opportunities. The slow fashion brand‟s attributes attract ethical consumers. The ethical consumer considers the impact of consumption in terms of environmental and social responsibilities (Barnett et al., 2005). The likeliness of ethical consumer‟s purchasing or willing to purchase a slow fashion product depends on the customer‟s level of involvement. A consumer with high involvement who is willing to purchase the product at a higher price, is not attracted to mass fashion trends, and shows intent to purchase an apparel product for environmental reasons (Jung & Jin, 2016). McNeil and Moore (McNeil & Moore, 2015) found correlations between concern levels for both environmental and social wellbeing and consumer‟s intentions towards sustainable apparel. Similarly, it is possible to predict the preference of ethical consumers to purchase a fast fashion product if made of sustainable fiber materials. Conclusions We analyzed the material-oriented trends of representative fast fashion brand, Zara, and slow fashion brand, People Tree, toward development of sustainable fashion. The kinds of materials used by each brand in manufacturing fashion products, and recent efforts in sustainable practices of both fashion brands were analyzed. The results indicated that the fast fashion brand, Zara has begun to incorporate sustainable fibers such as organic cotton into their products, and the slow fashion brand, People Tree uses more sustainable fibers such as Tencel and organic cotton for its garments and other products. The efforts involved in the trends of fast and slow fashion brands toward sustainable fashion were anticipated to attract ethical consumers‟ purchase intentions. The current findings suggested that new technology offers innovative manufacturing processes producing more eco-friendly products, less waste, and less pollution, which begins to mitigate the negative environmental effects of the traditional fast fashion industry. Implications and limitations This study was intended to analyze the efforts involved in the production of fast fashion and slow fashion brands in aspect of fiber materials, toward the overall goal of sustainable practices. This study may be useful to designers, manufacturers, and retailers who hope to better understand the trend of sustainable practices of both fast and slow fashion brands. Since ethical consumers presumably prefer sustainable products, this study may help designers, manufacturers, and retailers establish optimized strategies tailored to such trends. This study has a limitation due to selection of a small number of brands, which prevents the generalization of the results to all fast and slow fashion brands.

4,000원

152.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.445-449

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Introduction The manufacturing of apparel is the third-largest industry in the world, generating $700 billion annually (Jacobo, 2016). However, over the last 20 years, the US has lost 90% of its apparel manufacturing jobs (Bland, 2013). In response, the US Department of Commerce considers the importance of strengthening American manufacturing to be a key piece of economic recovery. They stated that large manufacturers needed to play a key role in, “cultivating the capabilities of small firms in their supply chains and spurring cross-pollination of expertise across firms” (Supply Chain Innovation: Strengthening Small Manufacturing, 2015, p. 3). This National Science Foundation funded research investigates the development of new, small US cut and sew firms as providing a potentially important link with larger, urban firms in the US apparel manufacturing supply chain. The objectives of this qualitative research are to: 1) ascertain social as well as economic challenges to establishing viable cut and sew firms in two rural US communities; and 2) examine the emerging issues in the apparel manufacturing supply chain; and 3) build propositions for research directions. Theoretical framework From an economic-sociological perspective, business, organizations, are embedded in larger institutional environments (DiMaggio & Powel, 1983, Granovetter, 1985, Meyer & Rowan, 1977, Meyer & Scott, 1983). The firm is seen as a part of a social-economic system with strong ties to others that can offer both business advantages (Di Maggio & Powel, 1983) or disadvantages (Uzzi, 1997). Institutional theory thus links social and cultural meaning systems or norms to the business environment (Handelman & Arnold, 1999). An Institutional theoretical framework proposes that in the economic environment, there are norms or rules that participants are expected to comply with if the organizations involved are to receive support and achieve legitimacy (Arnold, Handelman, & Tigert, 1996). Business owners or managers strive to legitimize their businesses, thus elevating investors’, suppliers’, and potential collaborators’ confidence in their competency to provide the specified products or services. This theory provides a foundation for examining the process through which small startup businesses, particularly rural apparel cut and sew firms, balance economic strategic actions and adherence to societal norms internally within their community and externally across a variety of apparel supply chain businesses located in non-adjacent urban communities. Current approach and preliminary results Using the Institutional theoretical perspective, we follow the initial stages of development for two apparel cut and sew centers in rural communities and their navigation of new businesses into the apparel manufacturing industry. Prior to outsourcing of apparel, many small agricultural-based communities across the state had manufacturing centers that provided income for local community members. Community leaders have long sought ideas for returning light manufacturing to their communities for local investment, job creation, and economic growth. Rural county economic development officers set up community interest meetings to see if there was interest in addressing the apparel industry need for quick speed-to-market and greater quality control through domestic manufacturing located closer to company headquarters within the state. Meetings in two communities, located in the northeastern part of the state, generated interest from local investors who have recently moved to open cut and sew centers. Four additional communities, located in the southeastern section of the state, await proof-of-concept prior to moving forward. Given the larger plan for the centers, the concept of specialization in manufacturing was determined for growth and expansion across the state; thus, one center was focused on woven apparel production and the other on knit apparel production. Cooperation and collaboration were important business values to prevent price competition and to potentially provide fulfillment of large scale orders. Longitudinal approach and research questions To address the objectives of this early stage work we used a case study approach to capture information. Data was collected from US Census Bureau and from interviews with investors, managers, workers, large manufacturing management, industry specialists in sourcing and equipment, as well as individuals connected to economic development and Extension. Please see Table 1. summarizing case study findings and emerging themes. In addition to these findings we employ a method frequently found in the analysis of an institutional theoretical perspective known as event history analysis. In time, this study will measure the temporal and sequential unfolding of unique events that transform the interpretation and meaning of social and economic structures (Steel, 2005; Thorton & Ocasio, 2008). This method will enable accommodation of data at multiple levels of analysis involving the individual (members of the cut and sew centers), organizational (cut and sew center firms), and environment (community and industry interactions). Event history is used to assess the five elementary concepts of – state (dependent variable, cut and sew center continuance), event (defines the transitions or experiences of the cut and sew centers), duration (length of time), risk period (potential for exposure to the particular event), censoring (not experiencing the event) (Vermunt, 2007). Thus far, we have initial case study data and documentation of events for two newly established cut and sew centers, but will continue to collect data as four additional cut and sew centers evolve. The following research questions address the five elementary concepts. We address the following research questions in meeting Objective 1 of this study: RQ 1. What are the social institutional centered events and consequences? RQ 2. How do different economic organizations contribute to firm evolution? RQ 3. What risks are involved that could inhibit or enable firm development? To address Objective 2 of this study, we focus on the following research questions framed around emerging issues expected to shape the apparel industry: RQ 4. What are the local capabilities? RQ 5. What role does technology play in firm emergence and development? RQ 6. How does the speed to market capability evolve? RQ 7. What are the industry expectations for domestic apparel production? Implications Early analyses of the two cut and sew centers highlights commonalities that are central to Institutional theory. In partially addressing Research Questions 1 through 3, we have found that there are several emerging issues that stem from weak or delicate linkages of social and cultural meaning systems or norms to the business environment (Handelman & Arnold, 1999). Though the investors, managers, and workers desire to meet industry expectations, there is a gap between the localized perspective and industry perspectives with neither having a strong understanding as to how to return the production to a domestic process. Years of outsourcing have weakened linkages and knowledge has been lost. Training is needed in commercial sewing, creating connections to industry, sourcing trims, ownership of goods, and pricing the production. Thus, as proposed in an Institutional theoretical framework, there are norms or rules that participants are expected to comply with if the organizations involved are to receive support and achieve legitimacy; however in this business arena, the rules are no longer clearly established. Further, the embeddedness of the cut and sew firms in the communities, though appearing to be currently well supported, may be moved as the cut and sew firms gain linkages beyond the community. In addressing Research Questions 4 through 7, we have found that though the support from the local communities has been strong both socially and financially, the learning curve was steep for both of the cut and sew centers in working with clients and educating clients in the product development process of sample pattern to grading to marker making for production cutting as well as procuring thread, findings, labels, hangtags, and packaging for delivery to stores. The move from home sewing to commercial sewing has involved considerable training of the managers and workers. Training featured understanding of the different machines, threading, and tension issues to ensure quality standards for apparel construction. Collaboration was facilitated by a technical consultant’s interface with an industrial sewing supplier and equipment repair company. Training of one-piece flow manufacturing work improved timing efficiency and quality control. The technical consultant spent days on-site and sewing with the team to solve process flow problems and study quality control issues. Issues of timing and efficient production process revolved around changing thread and adjusting machine and stitch tension for various contracts. Issues also emerged in the supply chain of contract manufacturing. Many of the clients were not ready for production, either due to financial commitments or understanding of the process from designing sample lines to marketing apparel products to retail stores and consumers. This required a change in plans to market the cut and sew center directly to the industry. The industrial sewers were flexible with producing various knit or woven sewn products. Issues related to managing a domestic cut and sew facility involved ensuring that all components were received on time, planning time, and estimating the costs involved with fulfilling manufacturing contracts. Data collection continues as the two established centers advance and four additional centers launch in the next two years. From this initial data and to meet the third objective of this inductive research, we offer propositions that warrant further analyses as the cut and sew centers more through various phases of development. Data will be collected to address propositions. P1 The greater the agreement in norms or rules that guide the apparel supply chain process, the stronger the business relationships among contractors, manufacturers, and cut and sew centers. P2 Legitimization of rural community cut and sew centers among the more urban supply chain members will build collaboration and reduce perceived risk in competency to provide specified products or services. P3 Increased collaboration among rural cut and sew centers in terms of shared knowledge and resources will increase perceived economic benefits to the individual centers and to the rural communities.

4,000원

153.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

p.450

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Individuals use material possessions such as clothes as a means to express their individual predispositions, values and position in their social environment (Kaiser et al., 2001). Evidence indicates that various individual differences such as hormone levels, body image perception and a cosmopolitan orientation influence clothing choices (Eisenbruch et al., 2015, Frith and Gleeson, 2004, Gonzalez-Jimenez, 2016). Moreover, body satisfaction, body mass index and trait self-objectification determine if individuals choose clothes for specific purposes such as fashion, comfort or camouflage (Tiggemann and Andrew, 2012). However, while these studies have made an important step towards understanding the influence of individual characteristics on clothing choices, there is a lack of studies that investigate the role of individuals’ materialist tendencies and propensity to engage in social comparison. We extend prior research on clothing choices by examining the associations between individuals’ materialist tendencies and social comparison propensity with sought clothing functions (i.e., fashion, comfort, etc.). Findings show that materialist individuals seek clothing for specific functions such as fashion, individuality and assurance, while avoiding clothes designed for comfort. Individuals’ propensity to engage in social comparison is linked with choosing clothes for fashion, individuality and assurance, but not for camouflage and comfort. Our study confirms that materialism and social comparison drive individuals to seek very specific clothing functions. Specifically, findings suggest that individuals use specific clothing types as a medium to establish their position in a social environment and to express their materialistic tendencies. Gender influences the tested relationships.

154.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.451-455

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

The study investigated the relationship between body satisfaction and attitudes toward trendy clothing among men in Generation Y with fashion involvement being a mediator in that relationship. Findings suggested a negative relationship between body satisfaction and attitudes toward trendy clothing and a mediator role of fashion involvement.

4,000원

155.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.456-457

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Shopping at bricks-and-mortar stores is considered highly experiential. An ability to experience and physically interact with a product is a key benefit of shopping at offline stores. In an online shopping context where sensory experience is absent, researchers have looked at how mental imagery as an alternative to in-store sensory experience impact consumer decision-making (Yoo & Kim, 2014). However the role of mental imagery has been largely overlooked in the context of offline store shopping. While it is true that shopping at offline stores facilitates sensory experience, evidence from cognitive neuropsychology literature supports that visual perception impacts visual mental imagery (Bartolomeo, 2002). Therefore, it is reasonable to posit that sensory experience in stores is related to mental imagery. Yet the relationship between actual sensory experience and mental imagery in the context of store shopping has not been studied. To fill a gap in the current literature, this study aims to examine the process by which sensory experience and mental imagery facilitate purchase decision-making in the context of offline stores. Based on the model of recursive relationships among consumers’ emotional, cognitive, perceptual and behavioral responses (Scherer, 2003) and a review of previous literature, this study posits that actual sensory experience and mental imagery related. It is further posited that both actual sensory experience and mental imagery influence consumers’ affective (anticipatory emotion) and cognitive responses (e.g., decision satisfaction, perceived ownership and decision satisfaction). This study employed an online survey in Korea. Apparel shoppers who shopped and purchased apparel at brick-and-mortar stores during the last six months were recruited. To facilitate a retrieval of in-store experiences, a series of questions about their specific shopping trip and purchases were asked at the beginning of survey. The current study consists of measurements adopted from the existing literature with adequate reliabilities. All the items were measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale. A total of 455 respondents completed the online survey questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were examined to assess reliabilities of the measures, and reliability coefficients were acceptable for all constructs (.78 ~ .92). Results of the SEM revealed that all the model-fit indexes exceeded their respective common acceptance levels, suggesting that the proposed model fitted the data well (2 = 627.38, df = 175; NFI = .92; IFI = .94; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .075). All the direct relationships among variables were significant except for the effect of sensory experience on perceived ownership, the effect of mental imagery on decision confidence, and the effect of perceived ownership on behavioral intention. This study provides new insights into consumer in-store shopping experiences and theoretical and practical implications. Sensory experience and mental imagery are complementary in facilitating consumer in-store shopping experiences. In addition to the importance of sensory experience, this study provides empirical evidence to support the vital role of mental imagery in the context of in-store shopping. Visualizing a situation through vivid mental imagery combined with actual sensory experience will lead consumers to positive shopping outcomes. Further research is warranted to better understand how to optimize actual sensory experience and mental imagery to offer excellent in-store experiences.

156.

2017.07

구독 인증기관 무료, 개인회원 유료

THE EFFECTS OF THE MOBILE SNS EXPERIENCE ON VALUE CO-CREATION BEHAVIOURS AND CUSTOMER LIFETIME VALUE

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.458-462

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

This study aims to examine how the mobile social network service experience affects value co-creation and customer lifetime value. The mobile social network service experience includes mobile convenience, social compatibility, social risk, and cognitive effort. The research hypotheses with structural equation modeling are tested. In mobile SNS context, value co-creation behaviors essentially determine customer lifetime value of mobile shopping apps. Value co-creation behaviors have received little attention in mobile shopping. The mobile SNS experience strongly influences value co-creation behaviors. This study is based on a sample of mobile SNS users nationwide in Korea. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings has to be tested. Furthermore, the study examines customer lifetime value, which is good sales predictor of mobile shopping apps. Moreover, the research model included the positive and negative determinants on mobile SNS experience. Future researches examine other use intentions of mobile SNS. Value co-creation behaviors substantially affect customer lifetime value. Mobile shopping apps should increase customer lifetime value from mobile SNS experience and value co-creation. This study shows how individual mobile SNS user provides mobile shopping apps with profit through value co-creation. This study is the first to examine how mobile SNS users enhance value co-creation and how value cocreation behaviors affect customer lifetime value of mobile SNS users.

4,000원

157.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.463-464

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the usefulness of Flexible Logistics Strategy for coping with the difficulties that logistics industry encountered in the highly competitive market. We define a logistics network model that reflects the current logistics environment of the metropolitan area and suggest the Flexible Logistics Strategy. We investigate the efficiency of the logistics system by comparing the Flexible Vehicle Strategy with other logistics strategies at the various scenarios that can mirror the real world.

158.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.465-466

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

This exploratory research focuses on variety-seeking behavior in the e-commerce (EC) apparel market. The author introduces the causes of switching behavior through exploring different attributes such as product category, price range, and brand. The author discusses the definition of variety-seeker within relatively high price, high involvement, and less frequency category. Next, the author proposes a practical methodology to find different types of variety-seekers from transaction data and customer databases. Finally, the author identifies the characteristics of variety-seekers, including mobile device behavior and psychographics of customers. Having reviewed previous research, in this study, the author focuses on: (1) research of variety-seeking that leans toward the low price, low-involvement, and high-frequency category, (2) define and distinguish variables of variety-seeking, especially in fashion and EC websites, and (3) use of mobile channels in variety-seeking. Researchers and practitioners have studied variety-seeking behavior since the latter half of the 20th century. One of the earliest studies of variety-seeking behavior is by Tucker (1964), who proposed the exploratory behavior concept. Since then, variety-seeking behavior has been extensively researched, and it is considered the antithesis of brand loyalty. As introduced by Assael (1987), in his matrix on buying behavior types, variety-seeking occurs as a low-involvement behavior and in a relatively low-priced category (e.g., Inman, 2001). Therefore, the research on variety-seeking in a higher priced category, like fashion, is a relatively novel approach, when compared to other categories of consumer goods. Meanwhile, there are many variables in general transaction data and customer databases, such as product category and group level (large, medium, and small), brand, product attribute (color, size, gender), price, time, and store. However, much of the previous research considered brand-switching as a clue for distinguishing variety-seeking. Thus, there is little research that has considered every database variable, and defined variety-seeking in the fashion category. Recently, new research focusing on the apparel industry and EC websites has been published. For example, Ko, Kim, and Lee (2009) discussed mobile shopping for fashion products, where they proposed the concept of information-seeking. However, their research was based on questionnaires. For this review, discussing and developing a methodology to analyze variety-seeking in the EC fashion industry was necessary. Distinguishing variety-seekers in this area might be useful for retailers or manufacturers for category management or line expansion (e.g., Inman 2001). This study uses transaction data from fashion EC sites obtained from the 2016 Data Analytics Competition, which was sponsored by the Joint Association Study Group of Management Science. There were over 550,000 purchasing transactions, and approximately one million records of units purchased from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016. The number of customers was approximately 100,000, out of which around 3,000 answered the psychographic questionnaire. Every product was classified into 24 large groups and 226 small groups. The data covered approximately 6,500 brands across 900 shops. In this study, the author conducts three analyses. First, the author introduces the types of variety-seeking behavior into the data, which produces a distribution that resembles the shape of the Pareto distribution in terms of sales or frequency. Second, the author discusses how to distinguish variety-seekers. Brand-switching is the most important criterion of variety-seeking behavior; however, the author includes concepts such as price-seeking, category expansion, and purchase interval. Finally, the author introduces characteristics of variety-seekers with demographic and psychographic variables in order to discuss the factors that determine variety-seekers. For example, using large group switching and sales, the author distinguishes the variety-seekers (over 3,000 customers, that is, 3%). From analyzing demographic and psychographic variables, the author, then, attempts to specify the reasons for variety-seeking in the fashion category. Finally, the author confirms the differences between mobile device and PC channels. In the age of customer experience management, use of mobile device has an important role. The author demonstrates the relationship between mobile device use and variety-seeking behavior. However, this research has certain limitations. First, this exploratory research does not adopt a rigorous hypothesis testing approach. The second limitation pertains to data—if the author had web access log data and real channel purchase data, other indicators could have been calculated. However, despite these limitations, this research makes theoretical and practical contributions. First, using fashion EC website data, variety-seeking behavior could be observed in relatively high price and high-involvement categories. Second, the author proposes a simple method to distinguish variety-seekers. EC sites, in general, may have similar databases; therefore, this research has application possibilities. Third, the author explains how psychographic characteristics and mobile channel usage of variety seekers could be beneficial for further research on variety-seeking behavior.

159.

2017.07

구독 인증기관·개인회원 무료

Global Fashion Management Conference

2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna

pp.467-468

글로벌지식마케팅경영학회

Introduction The concentration of manufacturing factories in China signals a significant change in the global economy. Manufacturers in countries that are not price competitive feel a sense of crisis and use servitization in the manufacturing industry as a countermeasure. In particular, with the recent rapid development of IoT and AI, service methods are becoming faster and more diverse resulting in increased research on servitization. Vandermerwe and Rada (1988), who first mentioned the term servitization, define it as providing customer-focused products, services, support, self-service, and knowledge, all bundled together. Despite numerous studies on servitization few consider the customer’s perspective, although many consider the producer’s point of view. So far existing research only explored on how consumers accept value-in-use based on an accurate understanding of consumers' needs from the consumer perspective in servitization, based on expectation-confirmation theory. This study examines how customers accept servitization and links it to customer satisfaction. Literature review Servitization Ren and Gregory (2007) defined servitization as a strategic change in which manufacturing companies develop service-oriented or better services to satisfy customers, gain competitive advantage, and improve corporate performance. Raja et al. (2013) examined servitization to find the most important attributes of value-in-use for customers using servitized products and classified them into seven attributes. This study is based on the seven attributes identified by Raja et al. (2013). Perceived Usefulness, Confirmation, and Customer Satisfaction Bhattacharjee developed the Continuance Use Model based on the expectation-confirmation theory and conducted empirical studies for verification (2001b). Our study analyzes the correlation between customer acceptance process and customer satisfaction based on the Expectation-Confirmation model by Bhattacharjee (2001b). Research method We conducted surveys and analyzed the data of 50 Korean university students and members of the public using Smart Pay (Samsung Pay, Apple Pay etc.). The reliability of the questionnaire was verified by using the Cronbach’s alpha values and exploratory factor analysis. The seven variables of the value-in-use attributes of servitization identified by Raja et al. are as follows: relational dynamic, accessibility, range of product and service offering, knowledge, price, delivery, and locality. We measured three additional variables: perceived usefulness, confirmation, and customer satisfaction. Contributions Academic contribution This study provides a theoretical basis for examining the relationship between variables and the influence of the value-in-use attributes of servitization on customer acceptance and satisfaction. Practical contribution We present implications for customer satisfaction in the servitization process of manufacturing companies by explaining how customers accept the value-in-use attributes of servitization.